Choice of game:

Ireland v United Arab Emirates at the Gabba (located in Kevin Pietersen's favourite city, Brisbane).

Ireland v United Arab Emirates at the Gabba (located in Kevin Pietersen's favourite city, Brisbane).

Team supported:

Ireland. Not only do I have Irish heritage, I also figured 100% of Ireland's cricketing faithful would not be able to make it to the match, and someone had to sing Ireland's Call in their stead. Hashtag Backing Green.

Ireland. Not only do I have Irish heritage, I also figured 100% of Ireland's cricketing faithful would not be able to make it to the match, and someone had to sing Ireland's Call in their stead. Hashtag Backing Green.

Key performer:

While his performance didn't contribute to a win, Shaiman Anwar's terrific century was easily the best innings of the day. Gary Wilson shepherded a difficult chase intelligently, and Kevin O'Brien's belligerence got Ireland into an ultimately winning position, but Anwar seemed to possess a little of both Wilson and O'Brien. Many of us guys and girls in green were assuming he was going to run out of time to make his hundred after a circumspect start. But some powerful late-innings strokes gave us a reason to celebrate. Presumably, the UAE fans enjoyed it too.

While his performance didn't contribute to a win, Shaiman Anwar's terrific century was easily the best innings of the day. Gary Wilson shepherded a difficult chase intelligently, and Kevin O'Brien's belligerence got Ireland into an ultimately winning position, but Anwar seemed to possess a little of both Wilson and O'Brien. Many of us guys and girls in green were assuming he was going to run out of time to make his hundred after a circumspect start. But some powerful late-innings strokes gave us a reason to celebrate. Presumably, the UAE fans enjoyed it too.

One thing I'd have changed about the match:

Is it wrong to berate Mother Nature when she answers our call? I attended the Australia v Bangladesh match in the rather naïve hope of seeing some action. My rant against the rain would have been heard at the other side of the stadium (because the echo was so distinct). Only a few days later, we spectators are blessed with a perfect Brisbane day (stifling humidity and all), and everybody spends it in the shade. It's too hot, we say.

Is it wrong to berate Mother Nature when she answers our call? I attended the Australia v Bangladesh match in the rather naïve hope of seeing some action. My rant against the rain would have been heard at the other side of the stadium (because the echo was so distinct). Only a few days later, we spectators are blessed with a perfect Brisbane day (stifling humidity and all), and everybody spends it in the shade. It's too hot, we say.

Face-off I relished:

Khurram Khan v Ireland. This man's batting prowess is not lost on those who know their Associate cricket. But I suspected the firmer wickets of the southern hemisphere would present a challenge, particularly against fast bowlers. As it happens, things didn't go according to this fan's pre-match script (one wonders why they're drafted at all). Ireland's spin attack performed admirably and, while the UAE were forced to consolidate after stumbling to 78 for 4, Khurram Khan's abundant skill evaporated into the scorching hot sun.

Khurram Khan v Ireland. This man's batting prowess is not lost on those who know their Associate cricket. But I suspected the firmer wickets of the southern hemisphere would present a challenge, particularly against fast bowlers. As it happens, things didn't go according to this fan's pre-match script (one wonders why they're drafted at all). Ireland's spin attack performed admirably and, while the UAE were forced to consolidate after stumbling to 78 for 4, Khurram Khan's abundant skill evaporated into the scorching hot sun.

Wow moment:

Kevin O'Brien produced two wow moments of contrasting styles. He unleashed some dodgy deliveries towards the end of the UAE innings, prompting those of us in the crowd to wonder why a bowler's variation has to be that variable. But that's the best thing about being an allrounder - you can still contribute. His duet of booming straight sixes brought the game back to life.

Kevin O'Brien produced two wow moments of contrasting styles. He unleashed some dodgy deliveries towards the end of the UAE innings, prompting those of us in the crowd to wonder why a bowler's variation has to be that variable. But that's the best thing about being an allrounder - you can still contribute. His duet of booming straight sixes brought the game back to life.

Close encounter:

Bail fail. The green contingent in the crowd experienced a gamut of emotions when that brightly lit bail didn't drop. Shock, acceptance, surprise, relief, joy. All in one minute.

Bail fail. The green contingent in the crowd experienced a gamut of emotions when that brightly lit bail didn't drop. Shock, acceptance, surprise, relief, joy. All in one minute.

Shot of the day:

Amjad Javed channelled some extraordinary players with his whip off the hip from the all-over-the-shop bowling of Kevin O'Brien in the 39th over. A little bit of Sir Viv Richards, a little bit of Aravinda de Silva and a lot of "Shut up, I wanna see this replay" was heard in the stands.

Amjad Javed channelled some extraordinary players with his whip off the hip from the all-over-the-shop bowling of Kevin O'Brien in the 39th over. A little bit of Sir Viv Richards, a little bit of Aravinda de Silva and a lot of "Shut up, I wanna see this replay" was heard in the stands.

Crowd meter:

Less than 6000 people enjoyed this match. I guess this is one of the reasons the ICC is whittling down future World Cups. But sitting among the Irish cricket faithful was always going to make the match more enjoyable, regardless of crowd numbers. We were camped next to like-minded fans from Penbroke Cricket Club (or Penbroke Cricket Clu, if read from their torn flag). Andrew Balbirnie was the number one star in their eyes, but this delightful group of fans were silenced after his dismissal for 30. They soon perked up as Ireland's chase hit the home stretch.

Less than 6000 people enjoyed this match. I guess this is one of the reasons the ICC is whittling down future World Cups. But sitting among the Irish cricket faithful was always going to make the match more enjoyable, regardless of crowd numbers. We were camped next to like-minded fans from Penbroke Cricket Club (or Penbroke Cricket Clu, if read from their torn flag). Andrew Balbirnie was the number one star in their eyes, but this delightful group of fans were silenced after his dismissal for 30. They soon perked up as Ireland's chase hit the home stretch.

Fancy dress index:

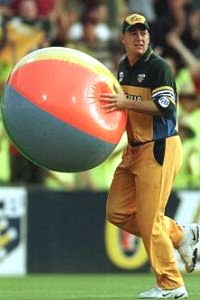

Despite the dedication of the UAE fans (who were barely visible from the other side of the ground), the points must go to Larry the Leprechaun. A man who can wear a polyester suit, fake red beard and impractical hat, relish the heat, sing all day and be a photo magnet has got my respect.

Despite the dedication of the UAE fans (who were barely visible from the other side of the ground), the points must go to Larry the Leprechaun. A man who can wear a polyester suit, fake red beard and impractical hat, relish the heat, sing all day and be a photo magnet has got my respect.

Entertainment:

Drummers kept pulses racing in those occasional ODI lulls. Warm applause greeted their renditions of Teenage Kicks and Enter Sandman, played in concert with the on-ground PA system. A few callous groans were reserved for any time a U2 song was played. I imagine those groaners have heard their last album.

Drummers kept pulses racing in those occasional ODI lulls. Warm applause greeted their renditions of Teenage Kicks and Enter Sandman, played in concert with the on-ground PA system. A few callous groans were reserved for any time a U2 song was played. I imagine those groaners have heard their last album.

Marks out of 10:

9 out of 10. All the griping about the heat knocks it down a little but frankly, complaining about the heat at the cricket is like complaining about the cold at the Winter Olympics. The day was littered with great people, a great atmosphere and a great match. And that's something the ICC can't afford to shrug from their shoulders. Associate nation cricket is exciting, and it should be here to stay.

9 out of 10. All the griping about the heat knocks it down a little but frankly, complaining about the heat at the cricket is like complaining about the cold at the Winter Olympics. The day was littered with great people, a great atmosphere and a great match. And that's something the ICC can't afford to shrug from their shoulders. Associate nation cricket is exciting, and it should be here to stay.

PS. Apparently, I was caught on camera wolfing down a chocolate ice cream. It brings to mind the episode of Seinfeld

where George is filmed making a pig of himself at the US Open. I hope

that footage doesn't come back to haunt me… Actually, make it 8 out of

10.

PS. Larry the Leprechaun got in touch with me via my now defunct Twitter account, appreciative of this article. Thanks Larry, thanks Ireland!